Should high school students have to ‘defend’ their diploma like a Ph.D?

California’s new way of ranking school performance could open the door to portfolio assessments

Seniors at Los Angeles High School of the Arts work on their graduation portfolios in Isabel Morales’s social studies class. LOS ANGELES — Looking smart in a blue button-down shirt, Jorge Magana, 18, zipped through a PowerPoint presentation with the confidence of a Fortune 500 CEO.

Seated in front of Magana in a classroom at Los Angeles High School of the Arts was a panel of three judges: the school’s assistant principal, a school coordinator, and a former student. The occasion was his senior defense. Magana was trying to convince the panel that he was ready to graduate.

He had 45 minutes to present a portfolio of three “artifacts,” one academic, one artistic, and one of his own choosing. The panel grilled him: Can you describe your research process? Which obstacles did you face and how did you overcome them? How will the skills you learned help with your future plans?

Portfolio assessments like this one, which look a lot like doctoral dissertation defenses, are on the rise in California. The practice, touted by educators nationwide as a proven path to college success, has largely been squeezed out by standardized tests, the quicker, less-costly measure of student performance. But the state’s reliance on test scores to rank school performance is about to change, and educators see an opportunity.

Since 1999, California has primarily tied school rankings to test scores, using the Academic Performance Index (API). Since its repeal in July 2013, the three-digit ranking has been undergoing revision. On the new API, which will debut in the 2015-2016 school year, test scores will account for only 60 percent of a school’s ranking. The other 40 percent will factor in graduation data and “proof of readiness for college and career.” Portfolio assessment can supply this data. The tricky part is convincing skeptics that these assessments are reliable.

Zaira Gutierrez puts the finishing touches on her graduation portfolio in Isabel Morales’s 12th grade social studies class at Los Angeles High School of the Arts.

Magana’s presentation seemed to come off smoothly. He started with the personal statement he wrote for AP English about his father’s alcoholism and its effect on his family. Then he presented a model of a set for the play “Electricidad” that he built for Advanced Scenic Design class. He finished with a policy memo he wrote for AP Government on the high cost of rehab.

But when the panel asked him specific questions, Magana stalled.

“What policies already exist to help those who can’t afford rehab?” asked Cathy Kwan, the high school coordinator who is developing the portfolio model. She schedules the defenses, recruits panel members, and trains teachers.

Magana fell silent and looked off to the side. He had just argued in the memo that the price tag for alcohol rehab is prohibitive for minimum wage earners and that there should be policies in place to ensure alcoholics can get the help they need free of charge.

“I did research that,” he said. “But I can’t remember.”

Magana stepped outside the classroom while the panel evaluated his performance. The judges agreed his presentation skills were solid: he made eye contact, he knew how to hold the audience’s attention, and he was organized. But he failed to demonstrate content knowledge and sound research skills. Assistant principal Matthew Hein pointed out a “classic bad research move,” Magana’s admission that he “dismissed research that didn’t fit his opinion.”

The verdict: Magana would have to rewrite the policy memo and defend his work again.

This is only the second year Los Angeles High School of the Arts has required its seniors to do portfolio defenses. The seriousness of the process and the amount of work it takes hasn’t yet sunk in. “Students didn’t really take the defenses seriously enough,” says Kwan reflecting on this year’s presentations. “They thought we were just going to let them pass. They’d say to me, ‘I got this.’ And I’d tell them, ‘No, you don’t. You have to practice.’”

Making Portfolio Assessments Reliable

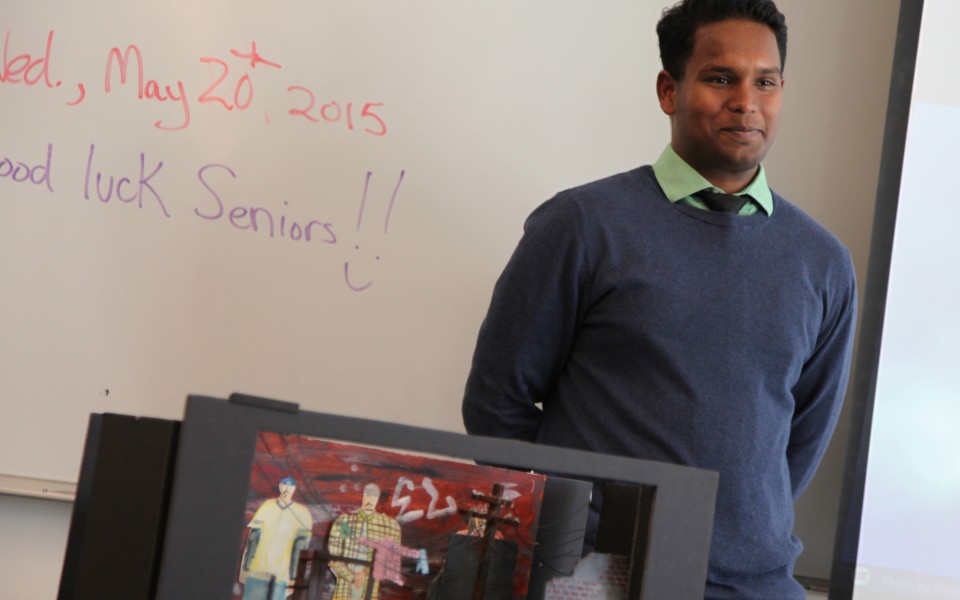

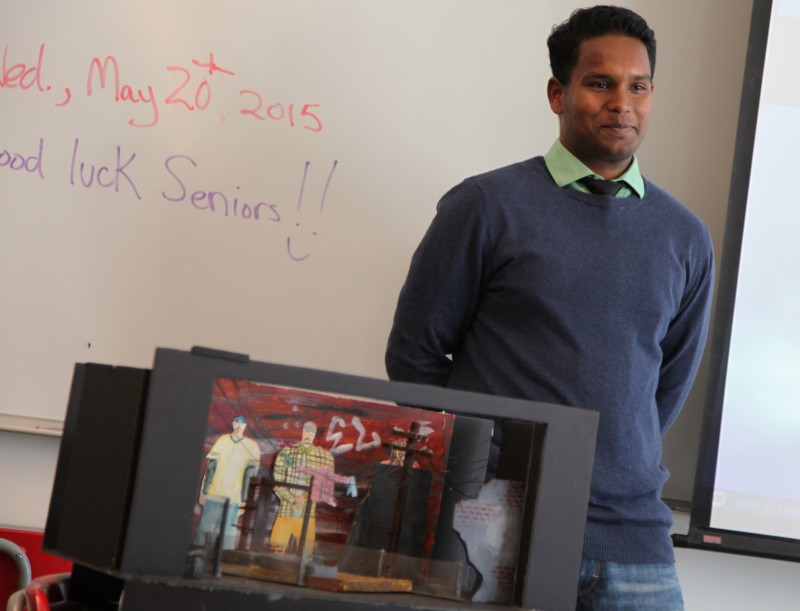

Cathy Kwan (middle) discusses a senior’s portfolio defense with assistant principal Matthew Hein (left) and Otoniel Ceballos, a recent graduate of Los Angeles High School of the Arts.

Kwan is struggling with the difficulty facing any educator hoping to use the portfolio model: defining a standard approach to evaluation. Harvard education professor Daniel Koretz knows this difficulty firsthand. He studied the portfolio models of Kentucky and Vermont in the 1990s, when those states were trying to replace standardized tests with portfolio assessments. The criteria for what makes a good portfolio, Koretz found, can vary widely from school to school, making comparisons difficult.

“The standardized assessment is standardized precisely so that there is nothing extraneous that differs between kids or between schools,” he says.

This problem has sent educators in California searching for an objectivity not usually associated with portfolio assessment.

A recent report from Stanford University professors Soung Bae and Linda Darling-Hammond promotes graduation portfolios as one measure of how well schools prepare students for college. The authors recommend that the state allow schools to use “well-designed” portfolios, comprised of work from each of five different subject areas to include research essays, art work and other sophisticated projects that can’t be captured on a test in place of traditional exit exams.

“There’s an openness in the legislature [to consider] what would be more indicative of college and career readiness than sitting down and filling in a multiple-choice Scantron,” says Darling-Hammond. “Some say U.S. kids are the most tested and the least examined in the world. We have a lot of tests, but we don’t have high-quality examinations of thinking and performance.”

Aiming to test the digital portfolio as a way of producing reliable data, Stanford’s Center for Assessment, Learning, and Equity (SCALE) has teamed up with ConnectEd, a Berkeley-based organization that promotes a mix of academic and career-centered school programs called “linked learning.”

Senior Raiyan Nasim beams as the panel judging his portfolio defense at Los Angeles High School of the Arts gives him a passing grade.

The resulting online tool, ConnectEd Studios, tries to take the subjectivity out of evaluating portfolios. Students can earn digital badges for completing performance tasks. A student writing an argumentative essay, for example, can upload the essay to the site, where his teacher can evaluate the writing according to a scoring rubric with criteria for grading. A series of dots represents the progress of the essay: red dot (ungraded), purple dot (not proficient), and green dot (proficient). When the essay is deemed proficient, the student earns a badge.

“We see these badges as data nuggets,” says Dave Yanofsky, director of strategic communications for ConnectEd. “If done right, digital badges give you both the qualitative and quantitative component. It’s not just that the student turned in the work and got a pat on the back. These badges show that students turned in work that is up to the level of quality we established.”

The development of reliable portfolio assessments could have huge implications for how we judge school effectiveness, not just in California but nationwide. Yanofsky estimates that 20 school districts, including Houston and Philadelphia, have expressed interest in working with ConnectEd to build their portfolio programs.

The expectation is that an online platform like ConnectEd Studios would create a secure place for students to share videos, audio files, photos, writing samples, digital badges, resumes, and letters of recommendation, showcasing their qualifications for universities and potential employers.

“Students can sell themselves short,” says Nadia Schafer, a digital specialist with Philadelphia Academies, a nonprofit that works with area high schools to provide students with career training and college preparation. “But the portfolio shows them all that they’ve accomplished. A portfolio tells their stories so much better than just a resume ever could.”

Related: Can we really prepare kids for both college and career?

Jorge Magana poses with his mother after earning a diploma from Los Angeles High School of the Arts. He failed his portfolio defense, but passed it on a second try.

For now, the goal at the Los Angeles Unified school district is to make the portfolio defense a graduation requirement. Ten high schools are piloting the initiative, and there are plans to get more schools on board next school year.

“Students have improved immensely since we first started,” says Kwan. “But it still wouldn’t be fair to hold them back based on the defense. We haven’t yet learned how to prepare kids adequately to do this.”

Half of the Los Angeles Unified schools testing portfolio defenses have partnered with Envision Schools, a network of three small charter high schools in the San Francisco area that has systematized the portfolio model over the past 13 years and can provide step-by-step instructions on how to build a portfolio program. L.A. teachers traveled to San Francisco to watch the Envision students’ defend their portfolios and to get training on how to critique them. Envision has shared videos of model defenses and scoring rubrics that L.A. teachers can revise to suit their schools’ specific needs.

Can Portfolios Make the Grade?

At first, many teachers at Los Angeles High School of the Arts thought the defense was an unnecessary torture. Then, they actually witnessed a defense.

“When you see your students reflect on what they’ve learned, and see how that learning has affected them, it’s hard to say this isn’t a good idea,” says Isabel Morales, a 12th grade social studies teacher. “Watching the defenses taught me how much my lessons count, how crucial it is for me to provide a transformative learning experience for my students.”

Morales says students can simply “go through the motions” in class, taking in information without really retaining it. But portfolio defenses force them to explain what they’ve learned, and to apply it in different ways; for instance, Magana tackled the issue of alcoholism as a statement on policy and in a personal statement. Since the portfolio program started, Morales has discovered that the best preparation for a portfolio defense is for students to share their work and reflections on what they learned in the process, something she didn’t always make time to do.

Realizations like this one are the most important outcomes of the defenses, according to Tom Skjervheim, associate director at ConnectEd. In fact, when Skjervheim views a defense, he finds himself evaluating the teacher more than the student. “The portfolio defenses shed a light for teachers on what they should be doing in professional development,” he says. “They allow teachers to think about how they might tighten up their practices and get the results they want from students.”

According to a survey of students at Los Angeles High School of the Arts, 90 percent of students who passed and 68 percent of students who failed said the portfolio defense was a “worthwhile experience.” Magana, who passed his second defense a week later, says he’s learned from his mistakes and won’t repeat them at the University of California Riverside, where he’ll major in computer science this fall.

“I’m worried that in college I won’t have anyone there to push me,” Magana says. “But I have this experience to refer back to. I will remember this. I won’t allow myself to fail again.”

Kwan is already planning ways to make the experience more worthwhile next year, including training teachers to revamp their lessons. She thinks teachers need to tell kids up front what they’re going to learn and why they’re learning it. “This isn’t as common as you might think,” says Kwan. “Kids often don’t know why they do assignments.”

Students will also get more opportunities to practice their presentations before the big day. Groups of four will be assigned a mentor teacher who will critique their portfolios and presentations. Eleventh graders will assist during senior defenses, by switching slides or serving as panelists, gaining a sense of what will be expected of them the next year. Tenth graders will participate in mini-defenses in front of their classes.

While Kwan is intent on perfecting the process, she worries that portfolio assessment could become rote in pursuit of data. The Envision Schools have the defenses “down to a science,” she says. Students start to sound robotic when they’re all saying the same things, she adds.

Success, for Kwan, depends on a continuous evaluation of the process, not on routine. What counts as a real demonstration of learning?

“Many visitors are impressed that students are speaking in front of an audience,” Kwan says. “They don’t notice that the presentation is disorganized or that the students are having trouble answering the judges’ questions. It’s not good enough that students face a difficult task. They have to go up there and have substance. Just because you show up to an interview doesn’t mean you get the job.”

Of the 92 seniors who defended their portfolios this year, 33 failed. Like Magana, they were scheduled to redo their presentations.

But, in the end, all students passed and nabbed diplomas.

“They worked their tushes off,” says Kwan. “Not one of them gave up.”

This story was written by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Read more about California schools.