Who Am I as a Teacher?

We teach and lead because God has called us to do so. For thousands of years God has asked people to participate in the work of helping others come to know God and live as people of faith. These teachers and leaders have come in many shapes and forms, from many backgrounds, and with many levels of ability. But each has somehow heard a call to teach and has responded.

You may not even realize that you responded to a call. You may think you merely answered a plea for help, or just knew it was your turn to help the third graders! But God’s call can come in many ways:

- through the voice of a friend

- through prayerful discernment

- from the challenge of a sermon

- by identifying your spiritual gifts

- upon seeing a need and responding

- through the strong movement of the Holy Spirit

- even by a seeming accident as you “fall” into teaching.

Take a brief inventory before exploring Basics of Teaching.

Read each statement; then circle the number that best describes your situation.

1 = Not at all; 2 = Somewhat; 3 = Mostly; 4 = Definitely

1 2 3 4 I understand that my teaching is in response to a call from God.

1 2 3 4 I know I never enter a classroom alone, for God is always present with me.

1 2 3 4 I understand that one of my primary roles as a teacher is to model the Christian faith to the best of my ability.

1 2 3 4 I believe the role of a teacher is not only to share information but also to create an environment where God can transform us into the people God wants us to be.

1 2 3 4 I understand how the primary task of the local congregation relates to my role as a teacher.

1 2 3 4 I know that people prefer different learning styles, and I am able to incorporate these different styles into my lesson plans.

1 2 3 4 I use a wide variety of methods in my teaching, and I am able to adapt them to the preferences of my class.

Why We Teach

Students, Participants, and Partners in Teaching

The Role of a Teacher

The Primary Task of Every Congregation

Many Ways to Teach

Using Curriculum Resources

WHY WE TEACH

You are called. Read the story of Moses’ call to leadership in Exodus 3:1–4:17. Notice some of Moses’ feelings and concerns that you also experienced when first asked to teach or lead. God’s call to you may not be as flashy as Moses’ call through a burning bush, but God’s need of you and God’s promise of support are just as strong as they were in biblical times.

Like Moses, your first reaction to a call may have been reluctance or fear. That’s normal. When God gives us a task, it can seem overwhelming and we may feel ill-equipped. Moses tried to argue with God and pointed out all of his own personal shortcomings. God assured Moses that his gifts were sufficient and that help would arrive when needed. Like Moses, we can be assured that God will use whatever skills we have and that we will find the help we need to be an effective teacher or leader.

God’s Presence

God does not call us and then leave us alone. As a teacher and spiritual leader, you have the promise that God will be with you. Story after story in the Bible tells us that God wants to be in relationship with us and to be present for us at all times. For example, “I will be with you,” God says to Moses in Exodus 3:12, and promises to help. When God sends Aaron to assist Moses, God adds, “I will . . . teach you what you shall do” (Exodus 4:15).

Jesus promised his followers that the Holy Spirit would be with them: “. . . I will ask the Father, and he will give you another Advocate, to be with you forever” (John 14:14-16). You can trust that God’s Spirit is present with you in the classroom, enabling you to accomplish things you could not do on your own.

A wise teacher once told a group of people who were learning how to teach that “God goes before me into every classroom I enter. God is present in that room before, during, and after I teach. I don’t have to do it all.” God is already present and working in the lives of the people you lead. God will continue to work within them long after you are no longer around. Thanks be to God!

God’s presence also assumes God’s grace. In church we often hear, sing, and read about the concept of grace. Very simply, grace means God’s loving concern for every person. There is nothing we can do to earn it; God simply loves us. There is no certain number of good deeds we must perform to qualify for it; we just receive it. Grace is the overwhelming, undeserved blessing of God’s love. It is this grace that surrounds us, supports us, and helps us lead and teach. You are not responsible for changing the lives of your students by your teaching; it is the God of grace who does this. You just tell the story of God’s love, and trust God to do the rest.

As a teacher you may encounter the term means of grace. This refers to an action or practice that is a channel for God’s grace. Means of grace are things we do that bring us into contact with God and open the possibility for us to grow closer to God. John Wesley, the founder of the Methodist movement, felt that each Christian (especially leaders) should be involved in these practices. The means of grace include (but are not limited to)

- prayer

- bible study

- worship

- Holy Communion

- fasting

- acts of service and compassion

- Christian conferencing (talking together about our faith)

As teachers and leaders we should be thinking about how we are personally involved in these means of grace and how we can help our students learn to practice them. The very act of teaching can be a means of grace. As we teach and as we open ourselves to learn, God’s mysterious work of grace happens; and all of us—teachers and learners alike—are transformed.

Dig Deeper: Personal Exercises

1.Reread and reflect on the Scriptures mentioned above. Use them in a devotional setting–let the words seep into your heart; look for the word of God to you. What do these stories and promises hold for you? Do you have experience of God in ways suggested by those passages? How is God calling you?

2.Look through The United Methodist Hymnal (or other hymnal used by your congregation). List the hymns that include the word grace. How is the word used? How do these hymns help you better understand the meaning of God’s grace?

For Further Study and Reflection

1.Gather with other teachers and small group leaders to share your stories and questions about how God has called you. What do you think God wants of each of you? What gifts do you see in yourself? Call forth and name the gifts and strengths you see in each other. Are any of those gifts complementary? How might you work together in different ways to enhance the teaching ministry?

2.Commit with other teachers to form a covenant group (for several weeks, at least) to study and consider prayerfully Three Simple Rules: A Wesleyan Way of Living, by Rueben P. Job (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 2007; available through Cokesbury). The third section specifically addresses the means of grace, but don’t skip the prior sections.

STUDENTS, PARTICIPANTS, AND PARTNERS IN TEACHING

No one comes to a class or small group completely “on empty.” The designated teacher not only has learners, but persons with something to offer as well.

A Cloud of Witnesses

Some of our best teachers are not immediately present. Who are some of the people who have been witnesses to the Christian faith? Who modeled or taught you what it means to be a follower of Christ? Thank God for their witness!

Hebrews 12 begins with the words, “Therefore, since we are surrounded by so great a cloud of witnesses . . .” This phrase follows a long listing of biblical people who were examples of faith. People like Abraham, Sarah, Moses, Esther, David, Mary, Paul, and many others not called by name— these people have gone before us and sought to be faithful to God. You can add other names to this list: people who are important in the history of your local congregation, pastors who guided you, parents who taught you the faith, Sunday school teachers who helped you grow. You are “surrounded” by these people when you seek to lead a group or teach a lesson. You can almost imagine them sitting in a balcony of your classroom cheering you on!

Class Members

Whether you teach three-year-old children or older adults, whether your group has two members or two hundred, you can know that the Holy Spirit is present. Jesus said, “For where two or three are gathered in my name, I am there among them” (Matthew 18:20). A teacher learns quickly that students and group members quite often “teach” the teacher. Group members come with a wealth of experience, knowledge, and backgrounds that one leader cannot provide. Often a student will share an insight that the leader has never thought about. Even the youngest learners can teach by the questions they ask and the different perspectives they bring to the subject at hand. A young child’s spontaneous hug and “I love you” can teach the teacher something about God’s grace. Teaching is a mutual process where all share together in the experience of teaching and learning. The older the student or group member, the more they bring and the more they expect to be allowed to bring.

The Congregation

You have been asked to teach on behalf of your congregation. Hopefully the congregation is supporting you by providing the space, study materials, and supplies you need to be effective. Other ways congregations can support teachers include

- providing prayer partners

- offering spiritual growth and study opportunities for teachers

- enlisting others to be substitute teachers or to serve on teaching teams

- providing training events in the local congregation and/or sending teachers to district and conference training events

- helping the entire congregation understand the value of the ministry of teaching.

If you would like to be supported in any of these ways, ask! Sometimes congregations just haven’t thought of all the possibilities.

The United Methodist Connection

United Methodist congregations are connected to one another in a special way. Local churches are joined together into districts; districts are joined into annual conferences; annual conferences are joined into jurisdictions; and jurisdictions are joined together with conferences outside the United States to make up the entire United Methodist denomination. The general agencies help support all of these different parts. Just as local congregations share their resources of money and service with these larger bodies, so the districts, conferences, and general agencies share their knowledge, resources, and skills with local congregations. Ask your pastor or Sunday school superintendent about training events and resources that might be available in your area. A district or conference staff person may be available to help provide training for teachers and leaders in your church. Perhaps several congregations located near one another could sponsor a joint learning event. General agencies provide written and internet-based resources that can be helpful.

Dig Deeper: Personal Exercises

1. Think more deeply about your own “cloud of witnesses.” What was it that made them good models and teachers? good spiritual mentors and leaders? Dig more deeply than, “She cared about me” to what it was that she did to demonstrate care or further than “the lessons were good” to what sort of preparation made them good. By delving more specifically into your reflections you can identify the success factors that you may be able to adopt and adapt. What have you learned that you can make your own?

2. Consider also the members of your class or group. What does each of them bring to the session? How might their knowledge and experience augment your own? What contributions have you missed so far that could add value to the rest of the group?

For Further Study and Reflection

1. Invite members of the congregation who are not currently in a class or group to meet together to share what inspiration, experience, gifts, strengths, or ideas they might contribute, on occasion, to the education ministry. Observers and past participants may have a perspective and gifts that need to be considered. Friends of the education ministry may be willing to be partners in some fashion, even if they are not present in a group each time it meets.

2. Call your conference office or go online to the conference web page to see what sort of helps are available.

THE ROLE OF A TEACHER

You have probably known someone in your life who was a truly gifted teacher. He or she seemed to have a deep knowledge of a subject, effortlessly knew what method to use, and was able to inspire others to learn. In fact, teaching is identified in the New Testament as one of the spiritual gifts given to people to be used in God’s service.

Many of us may never claim the title of gifted teacher, but all of us fill a teaching role at some point. Anytime we encourage, share information, guide, support, challenge, parent, or tell another about how God has acted in our lives, we are filling a teaching role. One resource states it this way:

In a real sense, every person in the congregation participates in the teaching ministry. We teach through worship, through service, through engagement in the administrative tasks of the church. Everyone in the congregation is both teacher and learner. (From Foundations: Shaping the Ministry of Christian Education in Your Congregation; copyright © 1993 Discipleship Resources; used by permission; page 4.)

One of the characteristics of a good teacher is being a good learner and a good listener. Teachers model for their students the value of learning. We can never learn all there is to know about teaching, nor will we ever have all the answers. Trust, value, and seek the wisdom of your class or group members. Listen to the questions and reflections of their hearts, knowledge, and experience.

Who do you consider the best teacher you ever experienced? What did he or she do that was so memorable or effective? It may be helpful to think of the following three words to describe your role as a teacher:

- model

- formation

- information

Model

A teacher is one who models the Christian faith, hopefully to the best of his or her ability. People learn by watching others’ actions and words. What we do is more powerful than what we say; how we live is stronger than how we claim we should live. Your students (of all ages) will watch you and learn from you. It is vital, then, that you model and teach well. The most powerful Christian teacher is one who not only recites, “Do to others as you would have them do to you” (Luke 6:31), but also actually practices it. An effective teacher is one whose faith is evidenced in his or her actions in the congregation and the community.

This does not mean that you cannot accept a teaching role until you are a perfect Christian. (If it did, our teaching ministry would have ended with Jesus!) It does mean that you understand the importance of seeking to grow into the likeness of Christ. A teacher should be growing in his or her own knowledge of the Bible, learning to pray, attending worship, and setting the example of a follower of Christ.

Formation

The role of a teacher of the faith is not just to pass on information or facts. It is to help people be formed as disciples (learners and followers) of Christ, and transformed into the people God has created them to be. Romans 12:2 says:

Do not be conformed to this world, but be transformed by the renewing of your minds, so that you may discern what is the will of God— what is good and acceptable and perfect.

Transformation is the process of being converted or changed so that our fullest humanity can be realized. Sometimes transformation is a slow process, like water rushing over rocks for years and slowly changing their shapes. Other times it seems to happen much more quickly, like a river flooding over its banks and radically altering the shape of the land. In either instance, transformation is the work of God in our lives that changes us more and more from our current state of being into the people God wants us to be.

The good news for teachers is that we are not responsible for this transformation—God is! A teacher’s role is only to create places, times, and atmosphere where people can learn about God, hear the stories of Christian people, experience Christian community, and talk about how God may want them to live in their everyday world. We trust God to do the rest.

Information

Part of the teaching responsibility is, indeed, to share information. There is more to learn about the Christian faith than any of us can ever know: information about the Bible and the stories in the Bible, the history of the church, theology (or how people think and talk about God), facts about the beliefs and practices of The United Methodist Church, and much more.

Much of the information you will share will come from printed study resources provided by your congregation. Other information will come from your own personal study and reflection. Your class or group members will also bring their collective and individual wisdom. No teacher will ever know all the answers. Yet we can help people learn some important information that will help them know what it means to be a Christian and will assist them in their walk with God.

Building Relationships

Perhaps one of the most important things a teacher can do is build relationships. A teacher first works to strengthen his or her relationship with God. Daily prayer and reflection, study of Scripture, participation in worship, involvement in service activities—these are just a few of the practices that can draw each of us closer to God. Next, a teacher seeks to develop a strong relationship with the students or group members in the class. Few Christians remember much of what a Sunday school teacher actually taught them. What they remember most is the warm and caring relationship with the teacher—or the lack thereof! A good teacher also pays attention to the relationships between members of the group, helping them build an open, supportive Christian community.

Dig Deeper: Personal Exercises

1. Consider how your class time is spent in information-giving.

- What do you do in your own class or group that informs?

- What proportion of your time together is spent in getting the facts?

- What emphasis is placed upon correct information? What happens when someone offers an answer that doesn’t square with the facts as you understand or present them?

2. Think next about how your class or group is structured to allow for formation and transformation.

- Do participants feel free to offer insights and to ask questions?

- Are all questions allowed or are there certain things “we don’t talk about in church!”?

- Is there time given in the group session for reflection or something “off the subject”?

- Is any part of the time spent for participants to reflect on what a text, comment, or Scripture means to them as a person of faith?

- Are participants challenged (in age-appropriate ways) to live out what they learn? If so, do you also help participants reflect on their service or other experiences in light of Scripture?

- Do you look for transformation and celebrate it when you see it?

- How are you developing your relationship with members of your class or group? What kind of relationship do they have with one another? What could you do to help?

For Further Study and Reflection

1. Gather the other teachers and group leaders together to explore the reference materials that each of you has. What is in your church library or pastor’s study that might be available to you? Do you search out information in sources other than the printed curriculum or study Bible notes? Commit to more background study as part of your preparation for a month or so to see what difference it makes in your teaching.

2. Work with the other teachers, especially those who work with the same approximate age-level, to discuss how they structure the class for transformation. What can you learn from and teach to the others? If you are unsure about how to structure your time to allow for transformation, consider joining with several other people for your own devotional time together (not primarily study time). Use candles or icons for focus; take time to pray silently and together; search the Scriptures for the service challenges they offer you and embrace something. Go back to the group to reflect on your own experiences and to explore how to set a similar stage in your learning setting.

- If you are an experienced teacher, consider being a mentor to a less experienced teacher. This could be in a formalized way, where you meet with the teacher on a regular basis to help him or her plan and to reflect upon what is happening in the classroom. Or it could be in a more informal process of sharing ideas, asking how things are going, or doing some joint activities.

THE PRIMARY TASK OF EVERY CONGREGATION

The primary task of every congregation is

- to reach out to welcome people where they are and to receive them as they are

- to relate them to God through Jesus Christ

- to nurture their growth in faith

- to send them into the world to live as disciples of Jesus Christ.

The primary task as described here is not four things, but one task with several dimensions. That one task can also be described as disciple making. The commission to be God’s partner in making disciples is the responsibility of every congregation. All the ministries, including the ministry of education and Christian formation, should align around what it means for your congregation to make disciples in its own time and context. Each ministry area, class, and group has a stake in disciple making. It may be someone else’s “job,” but it surely is your job.

Some groups will do one dimension more completely than others, and so the complementarity of all the groups and classes is important. Together, they engage in the primary task– all dimensions of it.

As a teacher or leader of a small group, you can pay attention to this primary task by

- creating a hospitable and welcoming atmosphere

- helping your group members come to know God and Jesus Christ by creating a safe place for them to talk about issues of faith and life

- encouraging your group members to grow and mature in faith through Bible study, discussion, learning activities, service, and worship

- sending your group members forth to live as Christian disciples in order to make the world more loving and just.

Each week you help your students reflect on how they live out their faith in the community. Then you send them out to begin the process again.

This may sound complicated, but it can be as simple as calling a child by name as he or she enters the room and giving the child a hug, telling your students stories about God and Jesus Christ, talking with your students about how a Christian tries to follow Jesus, then praying as you send your students out that each child, youth, and adult can find a way to help others in the name of Jesus.

Dig Deeper: Personal Exercises

1. Think about this primary task by rewriting it in your own words or by drawing an image or diagram of it. What examples do you see of each dimension in the church, over all?

2. List the things that you do in your class that relate to each part of the primary task. If you are not addressing each dimension, what’s missing? What can you do to engage that dimension?

For Further Study and Reflection

Gather with a group of other teachers or education leaders and study the portions of The Book of Discipline of The United Methodist Church (or the “marching orders” of your faith tradition) to gain further insight into the church’s mission and goals. How can you incorporate these understandings in your class or group and in the way you approach teaching?

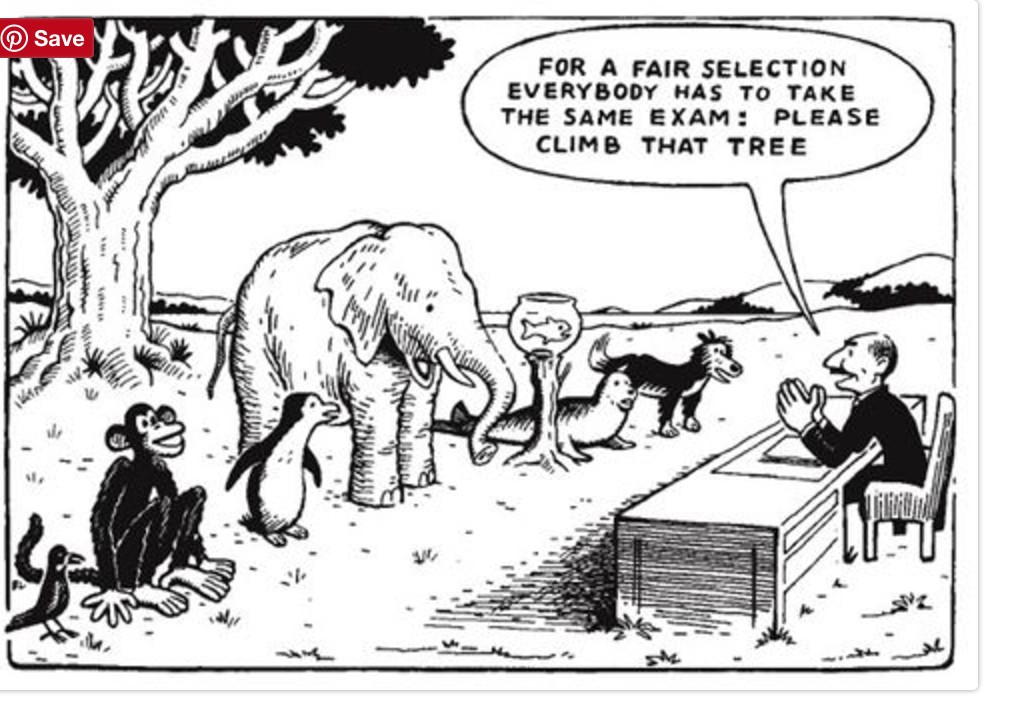

MANY WAYS TO TEACH

There are many different methods and activities to use in teaching and leading groups. There are entire books dedicated to explaining different ways to teach and learn. Most study resources designed for church classrooms suggest a number of different methods. Just remember that the most important person in deciding which method to use is not the teacher but the learner.

Ways People Learn

Listed below are a number of ways that individuals learn.

- Words: Learn through reading, speaking, discussing, and other language-based activities.

- Pictures: Learn through drawing, diagrams, and other visuals.

- Physical Experience: Learn through dance, athletics, games, drama, building, holding or manipulating objects, and other physical action.

- Music: Learn through singing, playing musical instruments, and other musical and rhythmic experiences.

- Numbers and Patterns: Learn through puzzles, experiments, and other activities involving logical analysis, sequences, and patterns.

- Self-Reflection: Learn through journaling, independent projects, and other reflective activities.

- Social Experience: Learn through group discussion, group projects, roleplay, and other activities that involve working together.

The Needs of the Learner

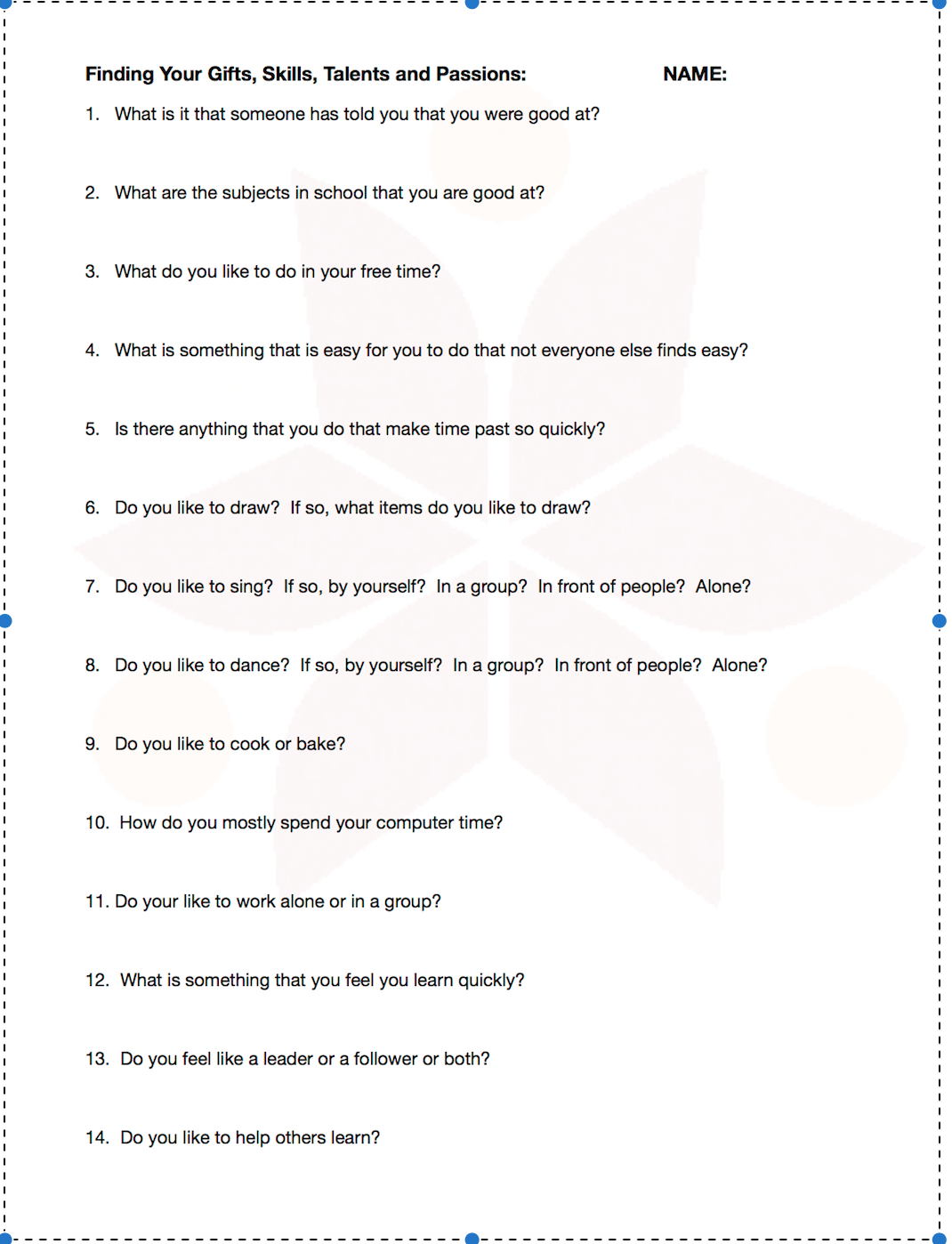

An effective teacher has a deep knowledge about the students he or she teaches. Only after reflecting on the answers to the following questions should a teacher decide which methods to use.

- What are the specific age-level characteristics of the people you teach? Can they read? Are they able to understand abstract concepts?

- What are the physical characteristics of your students? Do they need lots of space to move around and work off energy? Are study materials in large print helpful? Do any group members have special physical needs, such as wheelchair accessibility or assistance in hearing?

- What are the life concerns that your group members are experiencing—new parents? divorce? retirement? For what are they searching?

Choose a variety of different methods so that over several weeks you can meet the needs of all of your group members. Don’t be afraid to try new methods and approaches—you may find your students more responsive than you think. (See also the teaching methods in Using Curriculum Resources.)

When you have carefully considered the answers to these questions and thought about your students’ needs and preferred ways of learning, you will be much better prepared to choose methods and activities that will make the class come alive. Remember—you teach people, not lessons!

Dig Deeper: Personal Exercises

1. Take the time to jot down answers to the three questions above. What insights have emerged from a thoughtful consideration of these questions that helps you understand your group members better?

2. There are numerous inventories related to multiple intelligences (the ways people learn). Search the internet for “multiple intelligences” to find an inventory and complete it yourself. If your group members are old enough to understand and complete an inventory, print it and ask them to complete it. (To avoid copyright violation, record the results and discard the inventories. Do not share them beyond the class.) Use this information to evaluate your teaching methods.

For Further Study and Reflection

Go back to the list of ways people learn and place each class or group member’s name by the way that seems strongest for them; then record the lowest scores in the same way. (Remember that there is no right or wrong to this; it just is.) Next look back over your past few lessons. If you adapted or eliminated activities, in what category did they fall? Did you favor your own strongest learning style(s)? In future planning/ adapting, try to offer a blend of several methodologies, then ask your group members to evaluate the session.

USING CURRICULUM RESOURCES

Most study materials provide a number of different options for teaching and learning activities. You will want to pick and choose among these options in light of the preferences of your class and your own level of comfort and interest. But the resource materials are only the beginning point for your lesson plan. You must make the lesson plan your own.

Some teachers like to teach from the book or leader’s guide. Others prefer to write out their plan or outline on a separate piece of paper. It doesn’t really matter how you go about it. The important thing is for you to know the material well enough to focus more on what is happening in the room than on your notes.

Be flexible! You never know what might happen when we gather to learn in God’s presence. If the Spirit is moving in the room and people begin to share in a deep manner, let it happen. Don’t rush on to another activity because you planned it that way. On the other hand, if the method you thought people would enjoy and would take thirty minutes to complete turns out not to work at all and is over in ten minutes, move on to the next thing you have planned. Plan an extra activity or two that you can add if you need.

Variety of Methods

Here is a list of possible learning activities, methods, and aids.

- Audio tape

- Banners

- Bulletin board

- CD-ROM

- Clay

- Collage

- Computer games

- Creative writing:

- Cinquain poetry

- Haiku poetry

- Parables

- Debate

- Discussion:

- Total Group

- One-on-one

- Small group

- Circular response

- Question and answer

- Drama

- Drawing/painting

- Field trips

- Fingerpainting

- Group projects

- Guest speaker

- Internet

- Interpretive movement

- Journaling

- Lecture

- Listening

- Mock interview of Bible characters

- Movies

- Mural

- Musical instruments

- News report

- Open-ended questions

- Overhead projector

- Pantomime

- Paraphrasing Bible story

- Pictures

- Pipe cleaner sculpture

- Poster making

- Puppets

- Puzzle

- Questionnaire

- Quiz game

- Reading plays

- Reporting

- Roleplay

- Service projects

- Simulation game

- Singing

- Skits

- Slides

- Songwriting

- Storytelling

- Summary

- Timeline

- TV

- VCR

- Videos

- Wire sculpture

What a wonderful list of creative options! The problem is rarely, “What will I do?” but instead, “Which one of my options is better?” Remember, any of these methods can be effective if they are appropriate for the age level and needs of your group members and they are chosen because they will help people connect the good news of God’s love to their own particular life situations.

Dig Deeper: Personal Exercises

Look again at the list of methods and check any activity that you have used in the past. Using a different mark, check any method you want to know more about or might consider using in the future.

For Further Study and Reflection

1. Ask to have aDisciple orChristian Believer group (www.cokesbury.com) orCompanions in Christgroup in your church particularly for teachers and small group leaders who desire to deepen their own knowledge and faith life.

2. Start a study group for teachers and small group leaders using one or more of these teacher development resources, fromThe Upper Room bookstore,unless otherwise noted.

- Start Here: Teaching and Learning With Adults, by Barbara Bruce

- Our Spiritual Brain, by Barbara Bruce

- Loving God With all Your Mind, by Thomas Hawkins

- Teaching the Bible to Children, by Barbara Bruce (www.cokesbury.com)