-

SETH A. PARSONS (sparson5@gmu.edu) and STEPHANIE L. DODMAN are assistant professors in the College of Education and Human Development, George Mason University, Fairfax, Va. SARAH COHEN BURROWBRIDGE is a 6th-grade teacher at Lynbrook Elementary School, Springfield, Va.

Abstract

Students in today’s classrooms vary greatly in background, cultures, language proficiency, educational skills, and interests. To best meet students’ diverse needs, teachers must differentiate their instruction. The authors argue that the current differentiation conversation focuses almost exclusively on lesson planning, but instead should include important adaptations made in the midst of instruction — an aspect frequently overlooked or discouraged.

Differentiation shouldn’t end with planning but should continue as teachers adapt their instruction during lessons.

Students in today’s classrooms vary greatly in background, cultures, language proficiency, educational skills, and interests. To best meet students’ diverse needs, teachers must differentiate their instruction. The research base justifying the need for differentiation is strong (Santamaria, 2009; Tomlinson et al., 2003), and there is growing evidence that differentiated instruction has positive effects on student achievement (Rock, Gregg, Ellis, & Gable, 2008).

It is not surprising, then, that differentiation receives a lot of attention in teacher preparation programs, professional development efforts, and educational conferences. However, the differentiation conversation to date is missing a vital component, and we feel that current conceptions of differentiation are too narrow to capture the complexity of effective classroom instruction. Where the literature rightly details the role of planning in strong differentiated instruction, it almost wholly leaves out what can effectively happen during instruction.

Differentiation and planning

The educational literature on differentiation focuses on planning. For example, Gregory and Chapman described differentiation as “a philosophy that enables teachers to plan strategically in order to reach the needs of the diverse learners in classrooms today” (2001, p. x). Likewise, Tomlinson stated that differentiation requires an “alternate approach of instructional planning” (1999, p. 14). Lawrence-Brown conceptualized differentiated instruction as a “multilevel lesson planning system” (2004, p. 34). Moreover, foundations of differentiated instruction include such strategy created in instruction planning as curriculum compacting, flexible grouping, tiered activities, and student contracts (Brimijoin, 2005; Tomlinson, 2001).

Indeed, these perspectives and techniques describe effective practices and are helpful for supporting teachers in thinking about different ways to offer content, engage students in learning, and provide opportunities for varied end products. However, they provide a narrow view of the complex work of instruction to meet students’ diverse needs. We argue that the adaptations made in the midst of instruction are an important aspect of differentiation that is frequently overlooked or discouraged.

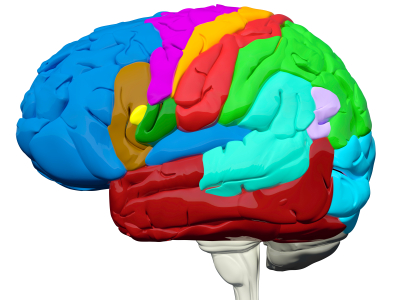

FIG. 1.

A broader view of differentiated instruction

Adaptive teaching as differentiation

Thoughtfully adaptive teachers adjust their instruction in real-time to meet the specific needs of individual students or the demands of the situation in which they find themselves (Fairbanks et al., 2010; Parsons, 2012). Therefore, teachers who effectively differentiate their instruction not only carefully plan instruction to differentiate for the variety of learners in their classrooms but also provide moment-by-moment adaptations to meet specific needs that become clear during instruction — needs that were not or could not be anticipated. Consider the following example.

The adaptations made in the midst of instruction are an important aspect of differentiation that is frequently overlooked or discouraged.

John Fox is planning to teach his 6th graders about adding and subtracting fractions. Aware of the curricula below his grade level, he knows students have at least been briefly introduced to this concept. To prepare for the unit, he gives students a preassessment to gauge their readiness. In planning the unit, he considers not only where students are academically, but also the multitude of learning preferences in the room. Based on this knowledge of students, he decides to begin with an introductory lesson on the basics of adding fractions and then sets up a variety of learning stations to practice the skill or deepen understanding. For the lesson, he groups students by their readiness to add fractions and assigns each to one of the following stations: using fraction manipulatives to solve problems, creating multistep fraction word problems, or playing fraction games. Fox feels satisfied in his differentiation of content and materials.

As students work in the stations, Fox circulates through the classroom observing and assessing students’ progress. Unanticipated issues arise. He immediately adapts instruction by pulling three students from two of the stations to correct a misunderstanding of the concept. Later, he notices that another student can’t match a written fraction to the corresponding fraction bar. He pulls this student for a one-on-one session on the basic concepts of fractions and then creates a simple task for the student to complete. Fox realizes that if the student does not understand the underlying concept of fractions, she isn’t ready to add fractions. This scenario shows differentiation in planning and in adaptive teaching.

Planning is the foundation of differentiated instruction, but a teacher cannot account for everything. Because student understanding is complex, even the most sensitive preassessment can only offer so much information. Teachers must be able to be responsive to unanticipated issues that arise when their differentiated plans are put into action. They must, then, be able to monitor student progress and adapt instruction based upon students’ needs and instructional situations (see Figure 1).

Advocates of differentiated instruction contend that reactive teaching is not differentiated instruction (Tomlinson et al. 2003), and we certainly agree. Instruction that is defined by a teacher planning one lesson for everyone and then trying in the moment to make adaptations when students indicate trouble is not differentiation; it is reaction. We agree with Tomlinson and colleagues that, “Effective differentiation will likely arise from consistent, reflective, and coherent efforts to address the full range of learner readiness, interest, and learning profile in presentation of information, student practice or sense making, and student expression of learning” (2003, p. 128).

Planning plus adapting

Teachers who effectively differentiate their instruction appear to possess three attributes. First, they consistently assess student progress in multiple ways. For example, in designing word study instruction, teachers typically administer a spelling inventory. The results of this inventory are used to create word study groups composed of students who are ready for instruction on particular word features (Bear, Invernizzi, Templeton, & Johnston, 2011). A 2nd-grade teacher, for example, may put one group of students to work on long vowel patterns, another group on blends and digraphs, and yet a third on compound words. Those groupings would have resulted from the teacher’s formal assessment and spelling inventory.

On the other hand, differentiating instruction by thoughtfully adapting during the midst of instruction requires teachers to use ongoing informal assessments to make informed instructional decisions. Wanda Jackson’s 8th-grade social studies classroom, which includes many Hispanic immigrants, serves as an example. She plans a lesson about Native Americans’ dependence on nature. Her objective is to illustrate how their surrounding environments shaped Native American cultures. She plans an introductory lesson followed by a read-aloud of an informational text on the role environment plays in our lives. She anticipates that the plan will engage students while meeting the objective.

Jackson begins the lesson with an orange, describing the trip the fruit took to get to their local supermarket. She wants to emphasize the stark difference between present-day life in America and the life of Native Americans during the 1700s. She asks students what types of food they would eat if they could only get food from the local area. A Honduran pupil who just entered the United States shares that she had never eaten an apple before coming to the U.S. The student explains that in her home country, very much like the Native Americans under discussion, people use strictly the material within close proximity to their village. Jackson asks if other students have had similar experiences, and seven other students raise their hands.

In this moment, she decides that these students’ stories are more powerful than the informational text she had planned to read aloud. She adapts her instruction by setting up sharing stations, where each of these students can share his/her experiences with other students in the class. This teacher has now differentiated the content of her lesson. This example demonstrates how informal assessments and spontaneous decision making help teachers differentiate their instruction to meet the unique needs of students and specific situations they confront.

A second trait of teachers who effectively differentiate instruction is that they have extensive knowledge about how students learn and effective pedagogy. Knowledge is frequently discussed in three dimensions: declarative, procedural, and conditional (Paris, Lipson, & Wixson, 1983; Schraw, 1998). Applied to teaching, declarative knowledge refers to knowing what is taught; procedural knowledge refers to knowing how to teach it; and conditional knowledge refers to knowing why one is using particular instructional practices and knowing when to use them. Planning differentiated instruction relies most upon declarative and procedural knowledge. A popular planned differentiation technique, a tic-tac-toe board, for instance, requires the teacher to use declarative and procedural knowledge. Because it is created in advance, though, this and other planned differentiation techniques rely minimally upon conditional knowledge.

On the other hand, differentiating on the fly by adapting one’s instruction requires well-developed conditional knowledge. If a particular form of instruction is not meeting students’ needs or a different form of instruction would be better for a specific situation, teachers need conditional knowledge to apply optimal instruction. In the example above, Jackson demonstrated effective use of conditional knowledge by changing her lesson from reading a book to allowing students to share their life experiences. Jackson made this shift after observing immigrant students’ sense of inclusion and importance as they willingly

Teachers who effectively differentiate their instruction:

shared their life experiences. She also saw the other students’ interest as they listened to their peers describe experiences similar to the Native American tribes they were studying. In order for all students to thrive, she knew she needed to foster a climate of acceptance in her classroom. Both lessons would have achieved the lesson objective, but Jackson used conditional knowledge to make a thoughtful adaptation that achieved much more.

The final characteristic of teachers who effectively differentiate their instruction is that they are highly reflective. Schön (1987) explains that practitioners, including teachers, engage in two types of reflection: reflection-on-action and reflection-in-action.

Reflection-on-action occurs after instruction is completed. Teachers reflect on what happened in the school day, and this reflection serves to inform subsequent instruction. Following a lesson, the teacher may reflect on what went well in her lesson and what challenges she faced. The teacher may choose to reuse strategies that proved successful or research new ways of teaching a topic area that created challenges for students.

On the other hand, reflection-in-action comes in the midst of teaching. This type of reflection informs adaptive teaching. Thoughtful adaptations require teachers to constantly observe student progress in order to make immediate changes or interventions. Teachers’ adaptability is honed by constant reflection: They enter each lesson with a clear plan to successfully teach a concept in a differentiated manner, but they are also ready to adapt if their best-laid plans are not sufficient for every child.

Teachers must be able and prepared to adapt their instruction in the midst of instruction.

Conclusion

As the diversity of the K-12 student population increases, it is critical that teachers differentiate their instruction to meet all students’ needs. Planning instruction that is based on individual student needs, interests, and learning profiles is crucial in differentiating instruction. Manipulating the content, process, and product of instruction facilitates differentiation. However, teachers also must be able and prepared to adapt their instruction in the midst of instruction. Exemplary teachers thoughtfully adapt their instruction to meet the diverse needs of students. Policy makers, administrators, professional developers, teacher educators, and school leaders can support teachers’ facility for differentiated instruction by valuing formal and informal assessments; emphasizing declarative, procedural, and conditional knowledge; and encouraging teachers to exercise reflection-on-action and reflection-in-action.

Learn. Teach. Lead.

Learn. Teach. Lead.

, which teachers and students can download for free online to use at home or in the classroom.

, which teachers and students can download for free online to use at home or in the classroom.