Do you struggle to draw the simplest of shapes? Or are you a seasoned artist who wants to go from good to great? Whatever your level, the drawing tips that follow will help you take your skills to the next level.

We dig deep into the science of how to draw better to uncover ways you can slowly but surely improve your drawing skills over time.

-

Practice makes Plastic – Harness Neuroplasticity to Improve your Skills

Since the 1970s, scientists have developed the now-standard theory of ‘neuroplasticity’ to describe learning and brain development in adults. Simply put, neuroplasticity means that our brains change their shape and structure as we learn new skills and information.

The more we practice a skill, the more our brain physically rearranges itself, strengthening the neural pathways which are required by that skill. This means that the more we draw, the more our brains optimize themselves for drawing. The messages for budding artists is simple – go forth and practice!

However, simply practicing blindly and stacking up drawing hours may not be enough. A scientific study into the development of drawing skills in students found that the best learners used a ‘strategic’ approach to learning.

These students identified their weaknesses, and found tried-and-tested methods to practice and improve them. They also tracked their the progress of their skills, and updated their practice methods accordingly.

The rest of this article outlines techniques for improving your drawing style, which you can apply strategically and practice often to plastically mold your brain into that of an artistic whizz.

Bottom line:

As with all skills, our brains adapt better to drawing the more we practice it. But it also helps to identify your weaknesses and focus your learning to improve them, as this will speed up your learning curve.

2. Get your eye and hand in sync

Scientists researching how humans draw have identified four factors that determine a person’s drawing abilities.

These are: 1) how well someone perceive objects, 2) how well they remember visual information, 3) what decisions they make as they draw and 4) how well they can coordinate their eyes and hands.

The latter – hand-eye coordination – is the most obvious, and is something beginners often struggle with. Luckily it’s very easy to practice!

Psychologists have long known how motor skills are improved. Performing a simple but challenging action repeatedly until it is mastered fixes it in the brain and makes it easy to recall for a long time later. As we learned previously about brain plasticity, this is because neural pathways are being physically strengthened within the brain.

Hand-eye coordination can therefore be improved by performing drawing exercises which are simple and easy to perform repeatedly and frequently, but provide tough challenges for hand-eye coordination.

To practice your hand-eye coordination when drawing from life, try ‘blind contour drawing’. Fix your gaze on the object you are drawing, and sketch it without looking at the paper.

This is a common trick used by artists to improve their hand-eye coordination skills. A few sessions of blind contour drawing can also help warm up at the beginning of a drawing session and get your hands and eyes in sync.

If you want even more of a challenge, you can try a variation of the ‘mirror drawing test’.

Mirror drawing is standard scientific test used in many studies on motor control skills learning and psychology, because of the unique challenge it presents for hand-eye co-ordination.

In the traditional laboratory setup, test subjects are asked to trace the outline of a star on a piece of paper. Their direct view of the paper and their drawing hand is blocked, but they are able to watch a reflection of the picture that they are drawing.

To practice this trick at home, prop up a small mirror beside you as you draw, and force yourself to only look down at your drawing through the mirror. The exercise will be challenging, but worth it for the coordination benefits it brings with repeated practice.

Summary

To improve your hand-eye coordination, try co-ordination challenges like blind drawing (drawing without looking down at the picture) and mirror-tracing (drawing while looking at a reflection of your drawing hand).

3. Fine tune your motor skills

Particularly if you like using a textured medium like painting, chalk, charcoal, ink or soft pencil, another crucial aspect of motor control in drawing is how to control the marks your drawing tool makes on the paper.

As all amateur painters know, different applications of pressure or angle can give vastly different textures or brushstrokes. As with blind contour drawing, the skill of working with tools can be molded plastically into our brain through practice.

A simple technique to improve your tool work which you can practice every day is simply to draw a series of straight lines, of equal width and a fixed width apart. Try to make the lines as uniform as possible – totally straight, the same thickness, and the same spacing between each line.

Slowly, your hand will learn how to control the tool in order to get the best line possible. This knowledge will be unconsciously absorbed, strengthening neural pathways and allowing these motor control skills to emerge during all the drawing you do.

Research has shown that the development of motor skills requires periods of rest between practices, when our brains can gather together and act on the information. Therefore it’s best to do this exercise little and often – practice it just once a day for as long as you can.

The bottom line:

Motor control skills are also important in the direct action of your tool on the paper. If you like work with a particular art tool – like a brush or chalk or embroidery machine – spend a short time every day drawing straight, precise lines to teach your hand the motor skills to control it.

4. Work on your short term drawing memory

Though it is the most obvious skill associated with drawing, hand-eye coordination is only part of what makes someone good at drawing. Scientists have found that artistic skills are dependent not just on our motor skills, but on our memories.

A study of 277 art students by University College London found that students with high artistic ability also had good visual memory.

When an artist draws something from memory or their own imagination, it obviously helps for them to be able to remember shapes and colours strongly.

But even when sketching real-life objects, a good visual memory helps the artist keep an image clear in their mind when they look down from their subject to the page. Without good short-term memory, their image of the object becomes muddled even in the short time it takes to glance down at the paper and sketch a few lines.

This may explain why many novice artists are frustrated when they look back up at their subject and find that it looks very different to what they have just drawn.

This type of short term memory is often distinguished in cognitive science by a separate term – ‘visualization’, or ‘working memory’. This is because the memory formation and recall occur so quickly they are almost unconscious, and they are not usual encoded to long-term memory.

This means that – luckily! – one does not need a perfectly photographic memory to be good at drawing. All one needs is an accurate enough working memory to keep a image in one’s head for a few seconds and commit it to paper.

A quick and effective way to improve your short-term working memory is the Copy Game. The game is simple:

- Find an image

- Look at it for 30 seconds

- Cover it up

- Draw it

When starting out, give yourself long time intervals (for example 30-40s) and use simple cartoon images. As your technique gets stronger, you can shorten your time and progress to more complex line drawings and photographs.

As with previous activities, the best way to pick up skills is to do them frequently in small amounts, over a long time. Work a quick version of the ‘copy game’ into your drawing routine or practice it every day.

No pen and paper to hand? Is there a way to improve your drawing even while crammed onto the subway?

There are a number of apps to hand which can help to improve your short term memory. In particular, a visual memory trainer by BrainHQ has been proven in an independent scientific study performed by UCSF researchers to help increase visual memory. Look in particular for its ‘mind’s eye’ app, which is specifically designed to target short-term visual memory.

Working at training your visual memory often is even more important as you get older. A study of over 55,000 individuals from the ages of 8 and 75 showed that short-term visual memory peaked at age 20 and declined sharply afterwards, with 55 year olds displaying even lower scores than 8 and 9 year olds. Fortunately, skills can be improved with practice at any age.

The bottom line:

Training your visual memory helps train your drawing skills. Boost these by playing a simple game of drawing images from memory, or downloading an app designed to aid short-term visual memory. Pay particular attention to this skill as you get older.

6. Learn what to choose

So you’ve learned to precisely control your hands, and fine-tune your visual memory. But there’s another crucial step which takes place between looking and drawing.

Several studies in drawing and cognition have found an intriguing factor which seems to distinguish good artists from bad: ‘visual selection’.

Real-world objects are infinitely complex, with countless dimensions, colours, shadows and planes to consider. When representing an object on paper with a small number of marks (i.e. when drawing!) the artist has to carefully select which parts of the object to emphasise and which to leave out.

Two studies (Kozbelt in 2010 & Ostrofsky in 2011) found that good artists were able to quickly identify the most important lines in a drawing. This allowed them to make an instantly recognizable image with a minimum number of lines.

Visual selection in one of these studies was evaluated using an unusual exercise: tape tracing. Participants were given a photograph of an elephant and asked to place a sheet of tracing paper over it. They were then given a number of short pieces of tape and asked to trace the shape with them. The photographs were then removed and the resulting ‘tape traces’ evaluated by independent observers.

The most skilled artists used their tape to identify the most important features of the elephant picture, including strong shadows and lines, while less skilled artists usually traced the outline of the picture without including relevant detail, or focused on ‘obvious details’ like the trunk and tusks, rather than key lines.

If you like, you can try the tape tracing game yourself to see how good your skills at visual selection really are.

An easier (and perhaps more enjoyable) technique, however, is simply to try to make a drawing using the least amount of ink (or pencil, or paint, or 3d penstrokes…) possible. Forcing yourself to be minimalist helps practice and reinforce selection skills.

If you have trouble keeping yourself to a few lines, try some timed drawing practices. Sit at your home office desk, give yourself 30 seconds to look at an object, and identify the parts of it which will be the most important to represent. Then spend the remaining 30 seconds drawing, not letting yourself make any last-minute embellishments.

The bottom line:

Good artists know what the most important parts of an image are to include. To hone this skill, practice creating an image with as few lines as possible.

7. Practice ‘Switching your Levels’

Identifying the most important parts of an object might help the artist plan their drawing. But these ‘important parts’ come in all sort of shapes, sizes and types.

The crucial parts of an image might range from the huge and general – like an object’s overall shape – to the small and delicate – like an important detail or texture.

A 2015 study found that successful artists had a high ability to switch between different ‘levels’ of an image, specifically between detail and general shape and form.

A good way to practice your visual level-switching is a parallel-drawing technique. Take an object with a strong external shape, and a detailed texture – say, for example, a sofa.

Take two sheets of paper and lay them parallel in front of you. On one, draw a sketch of the shape of the object, trying to get the large-scale form and dimensions as accurate as you can.

On the other, focus on shadows, patterns and textures, and try to capture minute and subtle details. Switch between the two every few seconds.

As you practice, you can start to work this technique into a single drawing. When you are drawing an object from life, consciously switch between focusing on the details and on the ‘big picture’.

This mimics the process used by professional artists, who keep their mind flexible while creating an object on paper.

Summary:

Learn how to ‘switch levels’ when drawing between large forms and shapes and small details. Train at first by switching between different drawings, and then consciously switching as you draw.

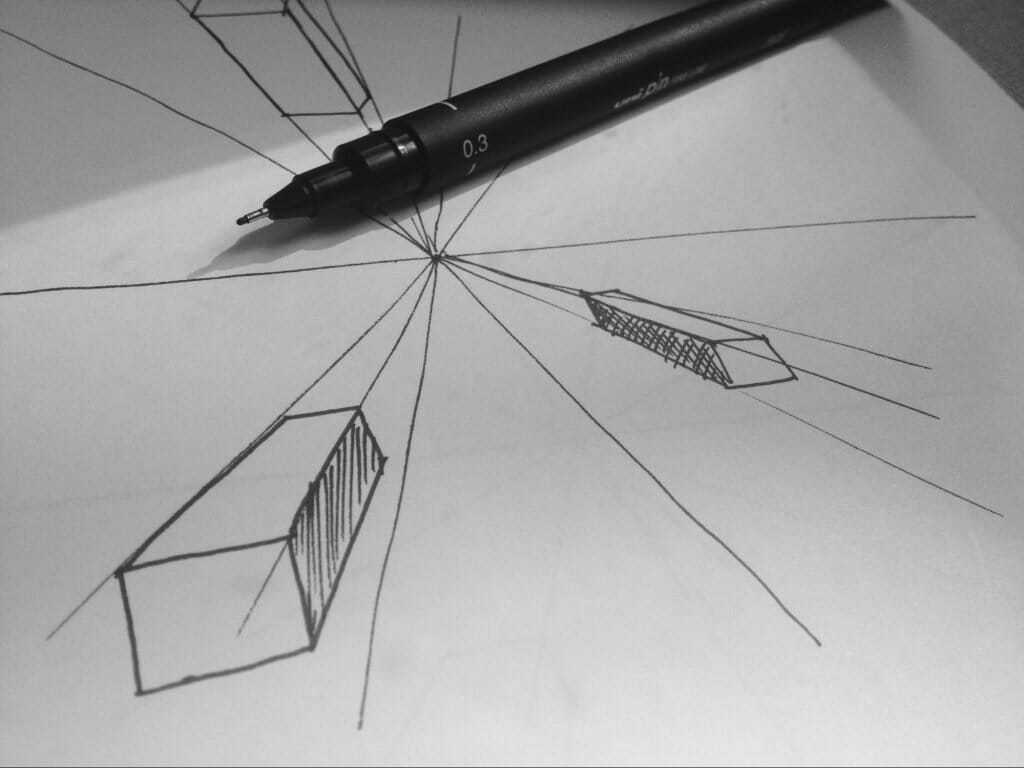

8. Play the ‘’perspective’’ game

Another extremely important quality of artists is high capacity for ‘object constancy’. This is defined by cognitive scientists as the ability to recognise an object even if it is tilted at an angle or moved closer or further away.

A 1997 study found that the most common cause of inaccuracies in drawing is not the artist’s motor skills or the decisions they make when drawing, but in fact their initial perception of the object. A further study in 2008 tested participants on an object-constancy test and found that those with a higher score had better drawing ability.

The biggest challenge in object-constancy for novice artists is often perspective. How do you distinguish between a small object which is close, and a large one which is far away?

Many art books and classes have a section on artistic perspective. This is a set of techniques, developed originally by Renaissance Italian artists, to give pictures a three-dimensional quality.

This technique involves drawing a ‘horizon line’ in a picture. Several ‘’vanishing points’ are defined on this line, and straight lines drawn emanating from these vanishing points.

Some useful guides to perspective drawing are available online.

This may seem a very technical and time-consuming way to approach drawing, but the good news is that you may not need to use this elaborate technique forever. Thanks to neuroplasticity, as with many other skills, the ability to draw in perspective will stick in your mind with enough repeated practice – something also proven by a separate scientific study.

One study has even suggested that drawing an object from multiple angles and perspectives has a positive effect on spatial ability in general, even beyond drawing.

To speed up your instinct for drawing in perspective, practice drawing small sketches on a perspective grid.

Draw a perspective grid on a piece of paper (or download some pre-drawn perspective grids) and choose a simple object like office furniture. Draw it at different points on the perspective grid and see if you can make it look like the same object.

As you build up your abilities you can try moving more and more complex objects around a perspective grid, and consciously try to incorporate the rules you learn into your drawings.

Summary:

Practice manipulating and scaling objects using a perspective grid to build up your instincts for ‘object constancy’ and how objects are positioned in space.

10. Practice scaling your drawings

This exercise may seem simple, but it involves many of the factors already mentioned – hand-eye coordination, visual memory and shape constancy.

Take two different sizes of paper, and draw the same object on them. The end goal of the exercise is to have drawings which are exactly the same in every aspect, but are different sizes on the paper.

This tests the artist’s ability to keep a consistent form in their head, even at different scales – activating the all-important visual memory pathways.

It also helps with another important skill in drawing; responding to the way your own drawing is developing.

Several studies have found that good artists are very aware of how their own drawings are progressing, and can change their strategies and approaches in response to small mistakes or opportunities they observe.

Drawing the same image at different scales forces the artist to perform this sort of course-correction, since they are constrained by having to keep the two images looking as similar as possible, and can’t ‘cheat’ by changing the dimensions of their image.

Summary:

Practice some of the skills mentioned earlier and hone your artistic decision-making by drawing the same picture at different scales

9. Draw the ‘’negative space’’ between objects

Improving your ability to perceive objects involves shaking up your perception and trying to see things in a new way. As discussed in the section on ‘level switching’, scientists recommend practicing any activity which disrupts the way the brain normally observes objects, and forces it to switch back and forth between different tactics

A good way to challenge your perception skills – recommended by drawing and cognition researcher Rebecca Chamberlain at the University of London – is to practice ‘’negative space’’ drawing.

When drawing a picture from observation, draw the spaces between objects instead of the objects themselves. This might seem tricky to understand, but think of it as drawing ‘gaps’ instead of ‘things’. The picture below – of two chairs – was drawn using the negative space technique.

The negative space technique trains the eye to focus purely on form, and prevents biases about what an object ‘should’ look like from creeping in.

It also forces the artist to concentrate on the distance between objects, improving understanding of perspective and space.

The bottom line:

Practice ‘negative space’ drawing – drawing the gaps between objects – as a way to hone your abilities at observing form and space.

10. Learn proportions

Many instructional art books teach about learning the proportion of different objects – particularly the common ratios present in human and animal bodies. This might seem to some like cheating – surely a good artist can just draw what he or she sees?

However, a recent study found a curious phenomenon. The study asked both trained artists and non-artists to draw portraits of a model. The non-artists consistently drew the model’s eyes too far up their heads, but were able to draw the subjects much more accurately when they were told that the human eyeline typically sits halfway down the face.

The reason for this is unexpected. As other studies have also found, humans have a ‘memory bias’ that affects the way we draw, even when our subject is right in front of us.

Humans have a series of unconscious images – not always correct – of what common objects such as people ‘should’ look like. It’s seems to be very difficult for us to discard this internal image and focus on the truth of what we are drawing unless we consciously make a decision to.

For example, in the study mentioned previously, scientists found that because the eyes are the topmost important feature of a human face, we think of them as being higher than they are, which works its way into our drawings.

The best way to beat these visual biases is through learning and practice – so swallow your pride and pick up a proportion guide.

If it’s good enough for Leonardo da Vinci (who’s own famous proportion guide the Vitruvian Man is world-famous) then it’s good enough for you!

Bottom Line:

Inherent cognitive biases can make us get the proportions of objects wrong, even if we are seasoned at drawing. Learning about proportions can actually help you overcome your biases and draw more accurately.

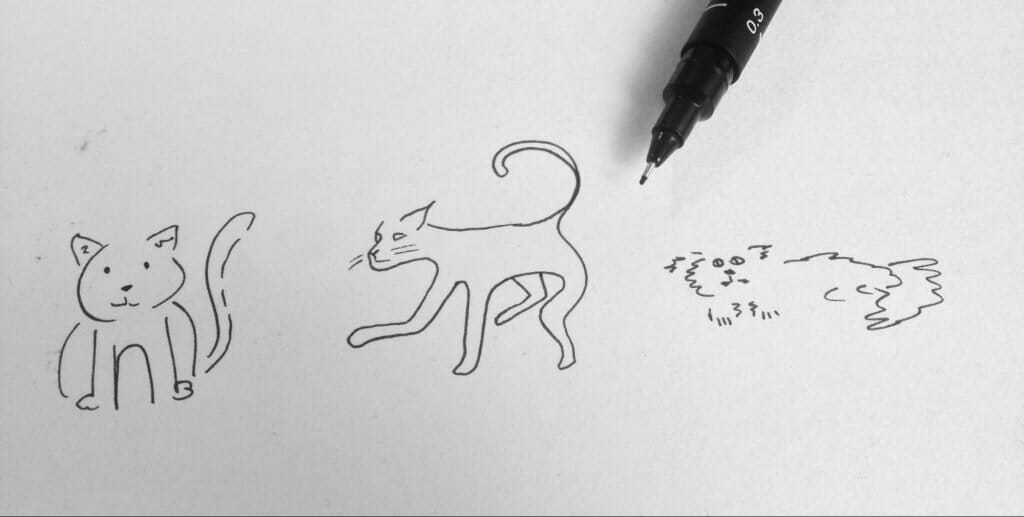

11. Divergent creativity: many ways to draw a cat

Not only can cognitive biases stop us from creating an accurate picture, they can also box us into fixed patterns when we are drawing creatively from our imagination.

Most of the topics so far have covered how to improve the accuracy and technique of your drawings, which is particularly important when drawing a real object from ‘life’.

But what if you also want to make your drawings stand out from the crowd? The best artists are able to combine precise technique with a vibrant imagination, allowing them to create entirely new images.

The science of what generates human creativity has been extensively studied in recent years. A particularly important component of creativity is “divergent thinking”, the ability to generate many different ideas based on the same theme or problem.

Studies have found that subjects who were given training in thinking divergently on a particular subject were able to improve their skills in that area in the long term.

The best way to improve your divergent creativity is to force yourself to generate many ideas. When drawing, you can do this by making yourself represent the same subject in many different ways.

First pick a simple subject you like to draw – let’s say a cat. Draw it.

Now try and draw the same cat, but make it as different as possible from the first. Can you use different line techniques? Emphasize different features? Make it more or less realistic? Place it in different positions, or angles?

Repeat this exercise as much as you can – try for a goal of ten different cats. If you get stuck, try to think of just one more variation, and let your brain really strain its creative ‘muscles’.

Finding different ways of drawing something trains your brain on divergent creativity in various ways – both in the creativity of visualizing images, and the creativity of the use of your drawing techniques. Continually drawing the same objects or in the same styles may even impair creative ability by not exercising the critical pathways required for divergent thinking.

The bottom line:

For creative drawing, improve your skills at generating new ideas by drawing the same subject in multiple different ways.

12. Enlist a friend for some ‘exquisite corpse’

Another great way to enhance your creativity is to enlist the help of a friend. Studies have shown that group environments can help generate more divergent and creative ideas, as group members build and develop on each other’s work (1), (2).

A well-known way of introducing group creativity into your drawing is the ‘exquisite corpse’ game. Invented by French surrealists in the early 20th century as a parlour game, the game requires players to create an image together by taking turns to add different pieces to the drawing, building on and adapting to others ideas.

A common form of the game is to draw a ‘monster’ – the first player draws the head of a creature, the next adds a body, then arms, legs and so on. In a more free-flowing version of the game, players simple draw whatever comes into their heads for a short time, and let their fellow players build on it.

As well as being a lot of fun, the game boosts creativity by making players draw within the constraints of others (psychological studies have also shown that having to work around constraints improves creativity), and take on board inspiration from others’ drawings.

The bottom line:

Working with others enhances creativity. Collaborate with friends to add features to an image in an ‘exquisite corpse’ game to harness the creativity of groups.

13. Steal like an artist

You’ve probably heard the often-quoted saying: “Bad artists borrow, great artists steal”, attributed variously to T.S. Eliot, Picasso and even Apple CEO Steve Jobs.

But recent studies into the neuroscience of creativity have found that looking at the works of others may indeed be essential to cultivating a creative mind.

Neurological studies into creative activity have found that exposure to ‘visual stimulation’ – a collection of diverse images – before a drawing activity led to more creative drawings being produced (3),(4).

fMRI scans performed during these studies also found that performing creative actions after receiving visual stimulus strengthened the functional connectivity of the medial prefrontal cortex, a connection pathway known to be essential for creative thought.

Another, very different study from the field of management science confirms that this exposure to visual stimuli is also valid in the ‘real world’, not just in the laboratory.

The study investigated professional artistic designers, and found that their creative output was greatly affected by the amount of time they spent looking at other examples of art and design as sources of inspiration. Negative impacts on creativity were found when their managers tried to limit the amount of time designers had to look at other work.

These studies lend scientific credence to those art-class trips to the museum – looking at art, particularly a wide diverse range of it – improves your own artistic and drawing skills.

The bottom line:

Exposure do the work of other artists and a wide range of visual stimuli strengthens neural pathways associated with creativity and helps generate original ideas. Exposure to visual stimuli is particularly effective right before drawing.

14. Look little, look often

Scientists attempting to discover the essence of what makes a good artist have performed studies in which experienced and novice artists are filmed while working. The footage is then examined discover the minute differences in their techniques which might hold the secret to artistic prowess.

In 2009, a study of this kind by John Tchalenko of the University of the Arts London confirmed studies by previous researchers and found that experienced artists used smaller line strokes and switched frequently between looking at their drawings and looking at their subjects.

Tchalenko and his colleagues theorize that this allows the brain to let the eye directly communicate with the hand, skipping the process of encoding the image to memory and then accessing it again.

It also makes the process of drawing more ‘fluid’ and natural, and allows frequent feedback so that the drawing can be quickly improved if a mistake is made.

This is not a technique present in many ‘How-to-Draw’ books. and is probably a skill that trained artists have learned instinctively based on their years of practice, rather than one that they have been formally taught.

However, now that it is been identified, it can be learned and harnessed by novice artists to help improve their skills.

So when you next draw, be conscious of how many times you are glancing between your paper and your drawing subject, and experiment with speeding up your glancing frequency..

The bottom line:

Experienced artists have learned to make short, frequent glances between the object they are drawing and their paper. Work this practice into your own technique when life-drawing.

14. Learn to take a pause

A study by Angela Brew, also from the University of the Arts London, found an important activity artists need to do when drawing: pause and think.

She recommends a technique in which artists pause briefly to stop and think about the next step required in their drawing. She found that this activity was much more common in the artists she observed than the non-artists, and led to better and more accurate drawings.

A separate study, which asked artists and non-artists to explain what they were doing as they drew, also found that professional artists spend a lot more time stepping back from their work and strategizing about what to do next. Untrained artists, perhaps out of nervousness, ploughed ahead and didn’t stop to think.

Trained artists also set specific goals at different points in their work. These could be, for example: “I need to make this part clearer” or “I want the shadows to be more distinct”.

Setting goals helps artists control the direction of their picture and correct mistakes as they go. It also reflects the importance of being bold and confident in drawing – when artists know what they want, clearer and more original drawings are produced.

The Bottom line:

Artists intersperse their work with pauses, in which they stop to reflect and plan on what they are doing. When drawing, take the time to stop and evaluate, and make goals for your drawing.

15. Enjoy it!

Now that you’ve read all this, perhaps reflect…why did you want to improve your drawing skills in the first place?

You might need improved drawing skills for professional reasons, but the majority of people who like to draw do so because it is enjoyable.

Now science has confirmed that it’s important to keep this motivation in mind, and not let your determination to improve your drawing skills cause you to lapse into negative thoughts or hypercriticism.

Happiness and positive thinking have found to be incredibly important in drawing. A study of artists and non-artists working revealed that trained artists had far more positive thoughts about their drawing as they worked, while non-artists were more critical and negative of their work.

This could be, of course, because the artists were able to produce work they liked.

However, it has been found that having positive thoughts while learning actually helps people pick up skills better. Studies of education have found that students learn better, and are able to remember what they have learned for longer, when they think positive thoughts.

On the other hand, several studies have confirmed that anger, anxiety, discomfort and other negative emotions have a significant negative impact on how quickly students are able to learn and their ability to remember skills.

So don’t stress, and remember that drawing is, at heart, about having fun.

The bottom line:

Thinking positively while drawing helps with picking up and retaining new skills, while negative thoughts make this more difficult. Have fun!