Hiring and retaining talented teachers can be a challenge in any district. But finding recent teaching college graduates who are ready to excel in the classroom their very first year can be even more difficult.

This leaves administrators continuing to question whether college teaching programs are adequately preparing each new generation of educators.

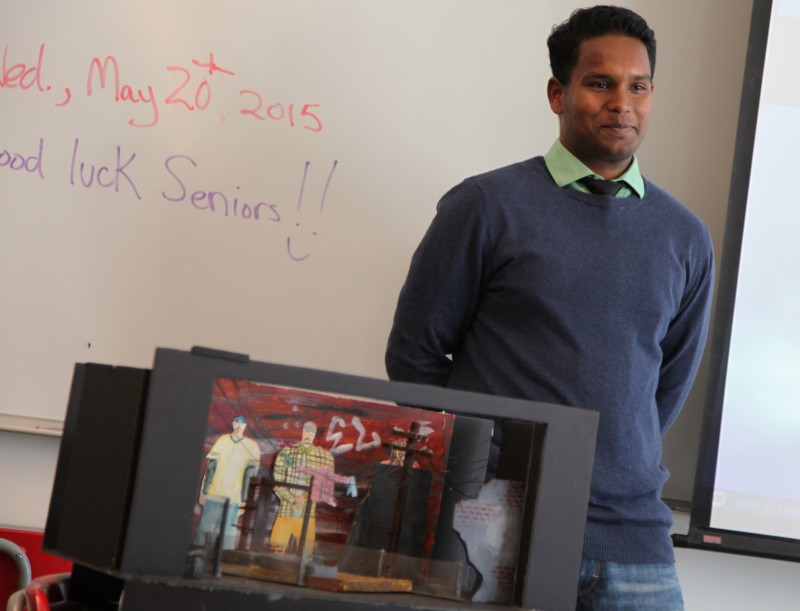

A successful prep program should be rigorous and purposeful, and get student-teachers into actual classrooms earlier rather than later, says Hamlet Hernandez, superintendent of Branford Public Schools in Connecticut and member of the District Administration Leadership Institute.

“Early and consistent classroom experience allows teacher students to see the role of management, routines and rituals in practice, and cannot be accomplished in a two-week field experience,” he says.

New teachers have historically struggled to manage their classrooms, says Hernandez. “Prep programs do not emphasize behavior management—the practice of recognizing how to mitigate different behaviors for different age groups.”

New teachers must be to able to precisely assess students’ ability to learn. They must also understand that students come to the classroom with different abilities, says Hernandez. “It is important for new teachers to know how to differentiate teaching practices, such as providing highly visual cues and clues for ELL students,” he says.

The colleges that produce successful teachers require early and frequent clinical work, integrate technology and set high standards for admission and grading.

Setting clear standards

Teachers-in-training must complete a preparation program during their undergraduate or post-grad master’s studies. States have different requirements for the level of education that must be completed; most require a student teaching experience and passage of a certification test.

Montclair State University in New Jersey produces effective teachers because its standards are clearly defined, says Susan Taylor, director of the Newark-Montclair Urban Teacher Residency. Taylor’s program pairs Montclair State teaching students with Newark Public Schools mentor teachers and classrooms.

Two views on the state of teacher prep programs

Some education experts have called for a massive overhaul of teaching colleges, claiming institutions are graduating students not ready for the classroom.

Yet others insist the colleges are doing a fine job, and that leaders from K12 schools and higher ed institutions simply need to collaborate more closely on how teachers should be prepared. Here are two opposing views:

Roderick Lucero, vice president for member engagement and support, American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education

- Teacher prep programs are doing a good job, and K12 schools should reject the notion that they and higher ed institutions are separate businesses.

- Teachers cannot graduate in May, start teaching in August and be “classroom ready.” Instead, they are ready to continue learning. Years of classroom experience will help a teacher be a better instructor.

- Reform is not needed, and the critics who are making headlines are not typically in the colleges or schools seeing what is really going on.

Kate Walsh, president, National Council on Teacher Quality

- Many education instructors are focused not on how well they’re preparing student-teachers but on research and publishing so they can get ahead in their own higher ed careers.

- Teachers arrive in classrooms not knowing what to do because they have been encouraged to develop their own teaching philosophies—but not trained in proven teaching methods.

- 97 percent of prep programs claim classroom management is taught. However, this instruction is limited to the notion that if teachers provide quality lessons, behavior won’t be a problem.

The university’s “Portrait of a Teacher” standards list 12 pieces of knowledge, skills and dispositions every graduate must develop. Included in the portrait is creating learning experiences that promote critical thinking and problem-solving; appreciating diversity among students and colleagues; and possessing strong literacy and communication skills.

When student-teachers practice job interviews or write essays, they must be guided by “Portrait” principles such as demonstrating expert knowledge of the discipline they will teach and promoting communication in the classroom.

The standards have made Montclair State’s student-teachers popular with local districts. Over the past five years, more than 100 of the student-teachers have been hired and retained by a local district, says Jennifer Robinson, director of the university’s Center Of Pedagogy.

Administrators get to know the candidates during their student teaching assignments and therefore have insight into their performance that cannot be gained when a random teacher comes in seeking a job.

“The student-teaching experience is like a 14-week job interview with highly effective candidates for the schools,” Robinson says.

The program at Western Governors University in Utah meets or exceeds every state’s standards for teacher prep to ensure all graduates are qualified to teach in any district in the nation.

The curriculum is competency-based, meaning graduates must demonstrate they have mastered each standard before they advance. Instead of earning credit hours and grades for a specific course taken during a set period of time, students take an assessment when they feel they have mastered a certain skill.

“If a student takes tests and does homework and gets a B in a specific course, what that represents is ambiguous,” says Phil Schmidt, dean of the Teachers College. “But at WGU, students demonstrate in a concrete way that they can lead a class.”

The Missouri Department of Education also sets clear standards. To ensure graduates are ready for the classroom, representatives from the Department of Education observe and grade students during their student-teaching on four highly critical standards: content knowledge, differentiating instruction, using data to inform instruction and classroom management.

“So all teacher colleges in Missouri know they must instill these skills in their students before student-teaching,” says Paul Katnik, Missouri’s assistant commissioner for education quality.

Prioritizing tech teaching

Just because today’s teaching students are digital natives does not mean they know how to use technology in the classroom, says Christina O’Connor, co-director of the Teachers Academy at University of North Carolina Greensboro.

“The current teacher prep students don’t have the benefit of observation because when they were students, teachers did not use technology as an instructional tool the way they do today,” O’Connor says.

University faculty integrate technology in teaching courses so students can observe how to use it in their future classrooms. Simulation software, for example, allows student-teachers to interact with virtual students and exercise the classroom management skills they are taught in their theory classes, such as quieting a noisy room.

Quality of teacher colleges

- Arizona State University: #1 for special education(undergraduate)

- Dallas Baptist University, Texas: #1 for elementary education (undergraduate)

- Western Governors University, Utah: #1 for secondary education (undergraduate)

- Montclair State University, New Jersey: #4 for secondary education (graduate)

Source: National Council on Teacher Quality Teacher Prep Review, 2014

“The level of disruption and types of misbehavior, such as a student pestering a peer, can be adjusted so the teacher students can practice all types of scenarios they may not see in their clinical experiences,” says O’Connor.

Student-teachers also observe their fellow student-teachers and veteran teachers on live streams from real Greensboro-area classrooms. “The class can have a discussion on what the educator is doing correctly or can improve on, and their commentary can be attached to the video so the observed educator can reflect on their own practices, too,” says O’Connor.

Meaningful clinical experience

At Arizona State University’s Mary Lou Fulton Teacher’s College, students fully immerse themselves in a K12 classroom during their senior year. “Instead of following the ASU calendar, our seniors follow their clinical district’s calendar,” says Cory Cooper, interim director for teacher preparation. “They arrive at their school two weeks early to prepare.”

In this model, the mentor teacher and student-teacher are considered co-teachers from the first day, says Cooper. They conduct parent-teacher conferences together and grade papers as a team. “When the student-teachers begin their first full-time teaching job, they are more like second-year teachers who know how to manage a classroom and use data,” Cooper adds.

To ensure positive experiences for student-teachers, a full-time supervisor from Arizona State visits each host school. The supervisor observes in the classroom to determine where student-teachers are struggling so the mentor can focus on building certain skills. The supervisors also offer professional development to mentors so they can effectively coach student-teachers to improve classroom management or content delivery skills, says Cooper.

Such methods appear to be working. Over 87 percent of Arizona State’s graduates remain in the teaching profession after three years, which is 7 percent higher than the national average, says Cooper.

Accept only the best

Only the best students from high school should be accepted into teaching programs, says Neil Duggar, dean of Dorothy M. Bush College of Education at Dallas Baptist University.

“The requirements for entry into our program exceed Texas standards and those of most other teacher prep programs to ensure we are getting top-performing students,” Duggar says.

Applicants to the College of Education must have a minimum 3.0 GPA, whereas the state requires only a 2.5 for teaching colleges.

Student-teachers prove themselves capable educators before entering a classroom for their clinical experience. “In addition to passing both Texas teaching certification tests, teacher students must teach a sample lesson to a panel of veteran teachers,” says Duggar. “If they are favorably scored, then they can begin their clinical teaching.”

Additionally, while Texas requires that student-teachers observe classrooms virtually for 30 hours prior to clinical teaching, Dallas Baptist students must watch for 220 hours.

Don’t be afraid of ‘training’

One of the biggest issues with teacher prep programs today is the overall fear of the word “training,” says Kate Walsh, president of the National Council on Teacher Quality.

“In the 1970s, it was decided that ‘training’ was a word that undervalued the complexity of education,” Walsh says.

It was feared that “training” would give teachers preconceptions about what students need. Training could create teachers who, rather than reflecting on the appropriate response, were more liable to pull a predetermined reaction from a set “bag of tricks” when, for example, a student spoke out of turn, says Walsh.

Yet for specific challenges, such as reaching growing populations of ELL and minority students, Walsh concludes, teachers need training in proven practices to provide meaningful praise and to establish rules and routines.

Kylie Lacey is associate editor.